A commenter on my blog mentioned her review over at Goodreads.com of To Have Loved & Lost, and, since I almost never visit Goodreads and therefore have very little notion of how my books are doing on that site, I decided maybe I should swing by and see what was going on. Rather to my surprise, I discovered that the #1 complaint with my book was…

The use of third-person present tense.

It turns out there are some true haters out there of the use of this tense — I mean, some people who *passionately* hate it. I never realized it was possible to get so emotional over the use of a tense. And I’m a doggone writer! LOL!

Personally, I like third-person present (obviously. I’ve written two novels in the tense!). I find it to have a kind of immediacy to it, an extra punch that draws the attention. And since the two novels I’ve written in that tense (oh wait — maybe it was two novels and one novella? Yes, I’m pretty sure Paradise is 3rd-p p, too) all involve characters who are dealing with / processing their pasts, it also makes sense to me to use present tense, because — and tell me if this makes sense — it’s like they’re all dealing with their pasts, but doing so very much in the NOW. That “now-ness” is why I like this tense.

And I like third-person present tense better than first-person present tense simply because… well, sometimes I want permission to write without perfectly encapsulating a character’s voice. Without writing from inside the character’s head. Writing in third person limited provides just enough distance; writing in present tense makes it feel like it’s still intimate.

But do you mind if I change the subject now and talk about Billy Corgan?

I heard him interviewed on Joe Rogan’s podcast. It was a long-ass interview, and some of it wasn’t that interesting to me, but what WAS interesting was Billy talking about what it’s like as an artist once your work becomes public and widely consumed. To me, that phenomenon presents an interesting, post-modern sort of question:

To whom does artwork belong?

Billy Corgan spent a lot of time talking about that with Joe Rogan:

Whether it’s a song, a novel, a painting, a movie — who owns the artwork? Does it belong to the creator? Or does it belong to those who consume it? — the listener, the reader, the looker, the viewer? Is art defined by its creator or by its consumers?

He talked about what it’s like to have a library of four hundred songs you’ve written, and when you do a concert, you want to play certain songs on a certain night. You want to produce a particular kind of experience for the audience, or express who you are that day or that month, by grouping a set of songs together.

But beware!

If you don’t play “1979,” your audience is going to *crucify* you. Because they didn’t come to your concert to hear those other 399 songs that you’ve written. They came to hear that ONE song, the song they lost their virginity to in the twelfth grade. To them, that’s THEIR song. And hearing you perform it? It’s more than just music they’re hearing. They hear a piece of their own lives that you, like a conjurer, allow them to experience again.

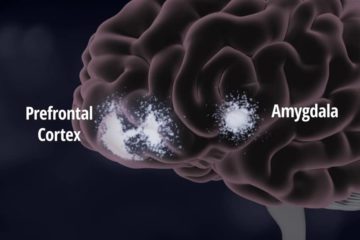

In the podcast, Billy talked about how uncomfortable it used to be for him when an audience wants to claim ownership of HIS work. His instinct for a long time, he said, was to say, “I don’t give a f*** if you lost your virginity to that song. It’s not yours. It’s MY g-d song. And you can’t tell me what I will or won’t do with it, or whether I will or won’t play it.”

Do you make art? — and not just any kind, but the soul-baring kind?

Every time I publish a novel, it’s like I’ve taken a small, naked piece of my soul and put it inside a display case for people to gawk at.

Now, listen: I’ve always understood that once I put a piece of writing into the world, it is no longer solely “mine” but belongs, at least in part, to the audience who consumes it. I’ve never believed that art is a static object — an inert collection of words or images or sounds. Real art should be something living: A pulsating, ever-evolving co-creation between artist and audience. And so from that point of view, I feel perfectly open to criticism, to accepting that not everyone will like what I write, or to accepting the fact that some people hate third-person present tense.

But from another point of view…

Well, it’s a little like watching a group of people crowd around that naked, vulnerable piece of your soul inside the display case and saying things like,

“Gah! It’s asymmetrical. I think asymmetrical souls are *so ugly.*”

When you write novels — or have anything that others can review within the public sphere, be it your business, your music, etc. — you HAVE TO accept that you’re going to hear criticism. You also HAVE TO accept that your work isn’t for everyone. Furthermore, you have to accept that not everything you produce is going to be stellar; sucking at creating art is just a part of the path to becoming a better artist.

But most of all, you have to accept that once your work is public, it is no longer simply “yours.” Art is neither the embodiment of the artist’s intention nor the sum total of the audience’s interpretation, but something caught forever in between the two — a conversation started by the artist but which the artist can no longer control or possess.

That’s a perfectly good thing.

But every novel I write is still a fragment of my soul, a kind of Horcrux designed to heal me rather than splinter me. So maybe readers would do well to remember that

Making art is an act of impressive vulnerability on the part of the artist.

it takes guts to express your grief, loneliness, guilt, and heartache, even if you do it through the medium of fictional characters. Even if those fictional characters find their jumping-off point in the form of fan fiction. Making art is brave. Making art public is both brave AND generous, because the most authentic pieces of art are also designed to be gifts to their audiences — a message in a bottle that, when the scroll is extracted and unfurled, reads simply, “And you? Yes: You are not alone.”

So the next time you comment on someone else’s soul at Goodreads, Amazon, YouTube, Facebook, Yelp!, or wherever else you like to post reviews, just keep that in mind.

And ask yourself if you’d be brave enough to put your own soul in a display case for others to judge and comment on.

—

And a PS to the Goodreads reviewer Candace: Yeah, you’re right. I shouldn’t use the word “nub” to describe a clitoris. In my own defense, I’m pretty sure it’s the only book I’ve ever used it in, but I’ll be more careful in the future. Writing about sex is, at least for me, very uncomfortable and very challenging. I will continue to try to get better at it.

4 Comments

Candace · January 26, 2018 at 6:11 am

Having written and published my own writing (my first novel got great reviews — all two of them), I do understand that feeling of nakedness. Hell, it’s taken me 30 years to write my second novel, in large part because I found myself so exposed in it that I set it aside for a good ten years. It took me that long to face up to the things I’d uncovered and work them through. And yet, and yet — anyone who reads a book or loves a song or spends hours staring at a painting _does_ own it, too, in a sense. I don’t think the consumers should get the royalties (grin), but it’s wrong to say that what we create isn’t theirs, too.

I understand why you’d want to use a pseudonym — that’s what I wanted to do, too, but back when I was published (1991), it was a time when it was important to be as out-there as possible (for reasons both political and LGBTI-Pride-related). So, having published under my own name, I feel I’m stuck with it. But I would think that using a pseudonym might make one feel a bit less naked and on display.

BTW, if it’s any consolation, I had no problem with the verb tenses/POV you’ve used in the Rosemont Duology. I’m a hypercritical reader with a professional eye (old editors never die, they just get damned cranky), and so if it didn’t bother me, I’m surprised it made anyone else crazy. Could it be some kind of literary fetish? I spent a few minutes researching the topic on the Internet, and some folks do seem to get their underwear in a twist about “TPPT.” My advice is to write your books in the voice that’s most comfortable for you. Maybe you’ll lose a few readers, but you’re doing good work, and that’s what will give your work longevity.

katrin Hornig · January 26, 2018 at 10:33 am

I think it is highly arrogant, to tell sombody, to do somthing, if i do not know anything

Thirt person.Hurt person.Hoe cares?It is your book and if you like you can writh in the 4 dimenson .

You do with it as you like and we can buy it ,or not .But it seems we like your books,or els we would not buy them.

The Real Person!

Well, it’s okay. People are entitled to their opinions and I’m fine with that. I just think that some of the things people get passionate about are strange. And especially to write a negative review about it. I mean, if you don’t like third person present tense, fine. But do you have to trash my book over it? People read reviews and take them seriously, and I think it’s kinda silly not to read a book just because you don’t like the tense. Or try to convince others not to read it.

The Real Person!

Thanks, Candace. I appreciated your kind words on Goodreads. You were generous with me.

Re: Nakedness. At some point I’ll need to share the WHOLE story about my pseudonym(s).