0 words so far written today; 126,839 total for the manuscript (which might actually be *lower* than my last update).

But the good news is, this happened:

Last weekend, I spent most of Saturday re-editing a holiday-ish-themed novella that was published in the charity collection Winter Hearts last year. Winter Hearts contained 13 short stories and novellas and raised over $7,000 split between two LGBTQ youth-centered charities (I think the one in the U.S. was the Trevor Project; I can’t remember which UK charity was chosen). Most of the other authors in the collection long ago released their short stories and novellas independently; I dragged my heels.

Mainly, I dragged my heels because it seemed silly to release a holiday-themed romance romp in the middle of the summer.

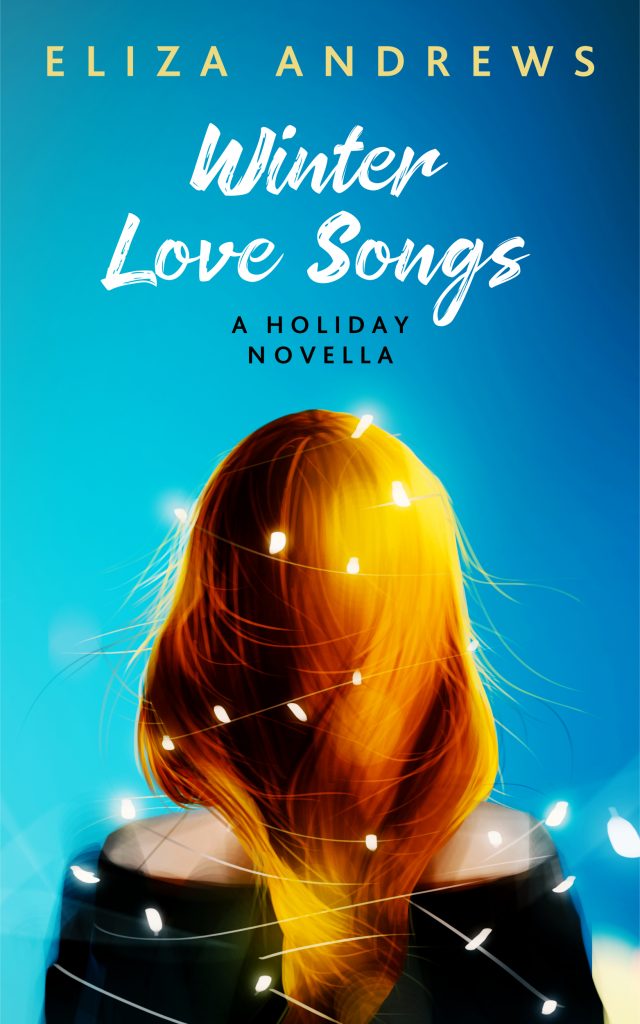

But last weekend, I finally got around to re-editing it, renaming it, and giving it a new cover.

Winter Love Songs is about what the title makes it sound like it is. It’s a short love story that unfolds primarily in the six weeks between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day. It’s not a very complex story full of twists and turns and deep themes and surprises, the way Reverie is. But at the same time, this is *me* we’re talking about, so it’s also not as fluffy as you might expect a holiday romance to be, either. About a quarter of the way through, there’s a major tragedy that one of the characters has to deal with, and that tragedy ends up driving the rest of the story.

In classic Eliza Andrews fashion, then, love me or hate me for it, it’s not *quite* as simple as a light-hearted romance. It’s *almost* that. It’s probably more light-hearted than 90 percent of what I write. But it still has that dark, trauma-driven element that I seem to always write about.

(Why do I always write about trauma, anyway? If you can figure it out, please let me know.)

Anyway, how about I share the first chapter with you? Then you can draw your own conclusions. Here:

1

June: “Turn the Page,” Bob Seger

HOPE CALDWELL

[ FIRST VERSE ]

There are three main things no one ever tells you about being a pop star, three things you only learn as you go and which sometimes make you wish you’d never picked up a guitar or sat down on a piano bench to begin with.

First: Once you make it big — and I mean really big — sell out stadiums, play the SuperBowl Halftime Show big — you will never have a moment to yourself ever again. Your life becomes a parade of people: managers, publicists, assistant publicists, make-up artists, assistant make-up artists, hair stylists, voice coaches, personal trainers, massage therapists, back-up singers, back-up dancers.

Morning, noon, night.

There’s a novelty to it at first, a kind of thrill when you realize that you’ve become someone who has an actual entourage. I didn’t even noticed it had happened to me until about five years ago, when I was backstage in Detroit. There were two hours to go before a major concert, and the hallways buzzed like an irritated ant hill. Dancers crammed themselves into costumes, musicians checked and double-checked their instruments, singers pressed fingers in their ears and hummed to themselves with their eyes shut, and stage managers in headsets and carrying clipboards rushed around shouting orders and answering questions.

I froze in the middle of it all. Shocked.

They were there because of me, I realized. Because of my music. Music I had written. And recorded. And made famous. Music that an enormous quantity of people in the English-speaking world, along with quite a few in the non-English-speaking world, had heard at least once. Music that got played on radio stations and at baseball games, backyard barbecues, birthday parties, grocery stores.

That night in Detroit, after so many years of toil and failure and frustration, it finally dawned on me that I was living out my girlhood dreams. In less than one hundred and twenty minutes, I would walk out onto a stage surrounded by a crowd that sounded like an ocean, each wave beating out a single sound, a single syllable — my name.

“Hope Hope Hope Hope Hope…”

And when they saw me, when I stepped into the blinding beam of the spotlight and the ocean became a roiling black silhouette made out of the shapes of tens of thousands of indistinguishable faces, my name would splinter into a cacophony of cheers and shouts and whistles and airhorns, and I would spread my arms wide, like Jesus granting his benediction, and the ocean would carry me away.

But that brings me to the second thing no one ever tells you about being a pop star.

You can be surrounded by an entourage, you can have your name chanted by a crowd of fifty thousand, you can be as recognizable in Bangkok as you are in Los Angeles, but none of it stops you from feeling more alone than you ever have in your life.

The third thing they don’t tell you is that there’s no going back.

#

Another fancy hotel room, permeated with that familiar, recently steam-cleaned smell.

Knock, knock.

The door to the adjoining suite squeaked open. A round face appeared in its crevice.

“Hey,” Charles said, and the deep rumble of his voice was a comforting, familiar sound in this unfamiliar city. “You okay in here? I thought I heard something.”

The television screen lit the room with undulating white light, and for a moment, I was reminded of what the lake looked like back home when the moon was full and the sky was clear. Silver moonlight bouncing off the black surface of the water, casting everything with a magical glow.

But it was just the TV.

I nodded. “Yeah. It’s fine. You probably just heard the television.”

And as if to underscore the point, Hollywood provided a deep space CGI explosion on the extra-large plasma screen TV hanging on the wall. I grabbed the remote and thumbed the volume down before the surround sound system could send the tumbler of bourbon sitting on the glass-top end table next to me rattling again.

“See?” I said to Charles.

His concerned expression softened, and he grinned at the TV set. “Outer space, huh? And here I was worried that your stalker had somehow gotten past me into your room.”

Affection surged in my heart for my burly bodyguard. Charles could be as overprotective as a mother hen sometimes.

“Come watch with me, if you want,” I said, gesturing at a spot on the stiff sofa beside me. “Aliens invade and the President fakes a diplomatic mission so he can plant a nuke on their ship.”

“I think I saw that one,” Charles said. He held up a phone through the half-open doorway. “And I’m on the phone with Margie.”

“Oh,” I said. Then yelled, “Hey, Margie! I’ll have him home to you in a week, I promise!”

I heard a faint, tinny laughter coming from Charles’s phone. It made me smile. I liked my bodyguard’s wife almost as much as I liked him. And once Charles had convinced her that I’m only interested in women and we weren’t ever going to have a Whitney Houston, Kevin Costner situation on our hands, she proved herself to be every bit as sweet and big-hearted as her husband.

“Have a good night, Hope,” Charles said, and the door to his part of the hotel room started to close.

“Charles?”

The door opened again and he gazed at me expectantly, waiting.

I hesitated. What I really wanted was someone to keep me company, to watch this stupid movie and make fun of it with me, but of course I couldn’t ask for that. Or I could ask for that, I supposed, but I didn’t want to be that pop star. The obnoxious, spoiled one who thinks that money and fame gives them the right to ask more from the people around them than they really should.

“Would you mind bringing me my guitar?” I said instead. “The old acoustic one with the stickers all over the case? I think they left it with some of the other luggage in your room.”

“Sure,” he said.

I muted the television set a few minutes later, sat forward on the sofa with the guitar in my lap. On screen, the U.S. President was crawling through an air duct on the alien ship, communicating via headset with the Vice President back in Washington.

I strummed a chord, humming.

Just me and my guitar. It was like that, in the beginning. Before there were back-up dancers. Before there was Charles, before there were hotel suites with multiple rooms. In the beginning it was just me on a makeshift stage in a dingy coffeeshop just off campus, guitar in my lap.

I leaned forward like I was talking into a mic.

“My uncle taught me this song,” I said softly into the pretend microphone. “He and my aunt, my mom’s sister, they raised me, and my uncle was the one who taught me to play guitar.” I strummed another chord. “I don’t know what happens to a person after they die,” I said. “But Uncle Billy, wherever you are, this one’s for you.”

I started in on the old Bob Seger song as quietly as I could, not wanting to disturb Charles’s conversation with Margie in the other room.

Out there in the spotlight you’re a million miles away

Every ounce of energy you try to give away

As the sweat pours out your body like the music that you play

I thought of stadiums as I whispered-sang, stadiums filled with a roiling ocean of silhouettes, each one of them wanting something from me, each one of them hoping I would fill something inside of them that they hadn’t yet filled for themselves.

Later in the evening as you lie awake in bed

With the echoes from the amplifiers ringin’ in your head

You smoke the day’s last cigarette, remembering what she said

I thought of the lake, walking distance from Uncle Billy and Aunt Tina’s house, and of dark summer nights lit only by the moon. I thought of the canoe, and the girl who sat in it, and how she pulled her paddle from the water, and how it thudded when she dropped it onto the canoe’s bottom.

I closed my eyes as I sang, remembering the way the canoe rocked as she leaned forward, cupped my face with gentle hands.

Ah, here I am, on a road again

There I am, up on the stage

Here I go, playing the star again

There I go, turn the page

Tears rolled down my cheeks as I reached the chorus. I didn’t know who I was crying for, exactly. For myself? For Uncle Billy?

For a girl. A girl in a canoe on a summer’s night in Georgia, cupping my face with gentle hands in the seconds before she kissed me for the first time.

“I love you,” she’d said.

There I go, turn the page

0 Comments