Greetings from the Denver airport, where I’ve been sitting at the terminal on my laptop, working on some odds & ends as I await my flight to sunny San Diego.

What I’ve been working on that you might be interested in:

- Setting up the details for a massive group lesfic sale I’m participating in later this month — Anika is going to be on sale for 99 cents in all countries for about a week

- Sending the contract to my narrator for the audio version of Anika, which should be done before Thanksgiving, yippee 😀

- Replying to a comment about gun control laws on a recent blog post I wrote

- Preparing this blog post and a couple more

Kind-hearted reviews from readers in the U.S. Maybe Americans don’t pay attention to cussing as much…?

But back to the f-word.

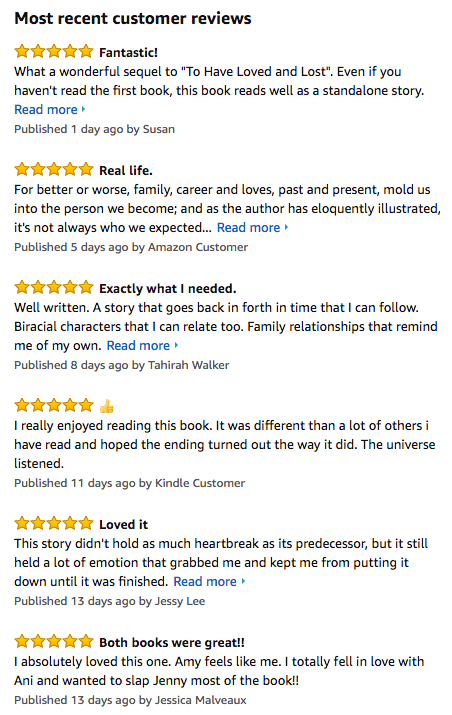

So, as I prepared for my sale of Anika takes the long way home up soul mountain, I had a chance to visit the book page in different countries on Amazon and found that I had a few negative reviews (I am a typical self-centered American who usually only visits the U.S. store, where I enjoy 50 current reviews with nearly all five stars — see the screenshot I took on the right.)

But in… Wait, was it Australia? or Canada? — anyway, I had this one-star review that was oddly complimentary of the story but complained mightily about Anika’s over-use of the f-word.

I knew some people wouldn’t like all the cussing. It’s why I specifically mentioned it in the book description. Some people have sensitive ears… or eyes, as the case may be.

LOL. Poor things.

The funny thing is, I don’t cuss. Like… at all.

I basically stopped cussing completely in my mid-twenties. I can’t remember the last time I uttered the f-word out-loud in a real sentence. If I get worked up enough — and I’ve gotten very worked up about politics in the last calendar year — I tend to say “frickin.” But the actual f-word…? Basically never. Sometimes I wonder if people read my books — because there’s a fair amount of cussing in To Have Loved & Lost, too — and think, “Geez. This lady has a real potty mouth!”

But I don’t. At all.

“Have I repressed all my bad language, and now it’s seeping out into my characters?”

This is the question I ask myself sometimes. Maybe almost twenty years of refraining from bad language has created a subterranean psychological pressure that seeks release and comes out through my fiction.

But I don’t really think that’s it. I think it’s more like this:

Are we all connected? Yes. Do we feel that way most of the time? No.

From one point of view, we are all inextricably connected and inseparable from one another.

Like individual droplets of water undulating against each other in a vast sea of life, every move we make affects everyone and everything around us, leading to a cascade of endless ripples whose reach is further than we can ever imagine. A smile we give to a stranger changes their mood just slightly, leading to her having a little more patience with her wife, who in turn goes to work feeling less stressed than usual, which allows her boss to relax, and prevents the boss from being short with the fast food cashier… and on and on and on.

This is the truth. But it doesn’t *feel* like the truth.

What *feels* like the truth is that we aren’t interconnected at all, but that we are each the Boy in the Bubble (or Girl, as the case may be, or Other). We navigate the world rolling around inside the impenetrable sphere of our own thoughts and feelings, bouncing against the impenetrable sphere of others’ thoughts and feelings, shouting through the impermeable barriers between us, hoping that at least a few of our thoughts make it to the other side.

This is how we *think* life is, most of the time.

Language is the mind manifest.

The only hope we have of making our innermost thoughts and emotions known and understood by others — the only hope we have of breaking through the bubble — is language.

Language isn’t just an aspect of our mind. It *is* our mind made visible.

Or at least: It is as close as we bumbling humans can come to being able to invite another bumbling human inside our bubble.

It’s one of the reasons why we love fiction, actually. In a story narrated by someone not-us, we have a chance to see the world from inside someone else’s bubble — and the experience is liberating. It’s like leaving the confines we’ve always been trapped inside and getting to roam free inside a new world.

Which is why the language choices a character makes is so important.

Until science thinks of a way to do it, language and story are currently the only methods we have of teleporting inside someone else’s head. The words we choose — or in a story, the words a character chooses to tell his or her story — are incredibly important, because each word is a portal into the character’s soul.

How do f-bombs invite us into Anika’s soul?

Who is Anika? She is a woman who grew up feeling like she was someone who constantly needed to defend herself. Not quite black, not quite Nepalese, but a hundred percent dyke, she perceived herself as being judged from all angles. Judged by white peers for being brown; judged by African Americans for not being “black enough;” judged by Nepalese as the product of a relationship that never should’ve happened. And meanwhile, judged by her religious mother for being gay.

Plus she was *huge* (for a woman). If she’d been a smaller person, she might’ve chosen to dissolve into the background and avoid the stares of others in the way we introverted wallflowers do. But her size didn’t give her that choice. Her size, together with the color of her skin and her dyke-ish-ness, ensured that she would always be a spectacle, no matter where she went.

So the attitude Anika adopted was a sort of belligerent, “So? You got something to say about it? Say it to my face.” She would “get them before they get me.” It was her coping mechanism for dealing with what felt like a hostile world, a hard outer shell to protect the gooey, sensitive center of her.

Her choice of language reflects that. She leans on abrasive words as an injured man leans on a cane.

So to the person who said:

I wouldn’t mind but, if in the authors mind, the constant use of the word is to demonstrate someone who’s on the edge, really cool, then it isn’t working for this bunny. Come on, I was using the f word and a whole lot more colourful words in school to the extent that they no longer had any impact.

my answer is, “LOL. No. It’s not to make Anika ‘edgy’ or ‘really cool.’ It is because Anika is Anika, both sensitive and hard at the same time, both liberated by her own tough attitude and helplessly trapped by it, and that unveils itself in the words she chooses and the cadence of her speech.”

Following characters around

People who don’t write fiction have this assumption that *authors* write stories. Authors know that, although it might sound strange or silly or stupid, a fully formed character writes her *own* story. All the author does is follow her around writing it down as quickly as possible.

I knew Anika cussed too much for a lot of readers. I knew it was going to turn people off. And believe me, I talked to her about it. I encouraged her to tone it down. (I also told her not to ramble so much.) But in the end, Anika is who she is unapologetically. And as her biographer, all I could do was represent her in the way she wanted to be represented.

You can believe me or not, but it’s the truth.

0 Comments