I am a white southerner from a historically privileged family.

There. I said it. It wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be.

Of course, like most Americans, my story is a little more complicated than that. I’m not accepted as a southerner because I didn’t (completely) grow up in the South. I don’t have the accent and I don’t have the southern pedigree; where I live, if you great-granddaddy didn’t grow up here, and then your granddaddy and your daddy after him, you’re not *really* from here. I am actually a Midwesterner who moved to rural Georgia shortly before I turned thirteen.

Plus I’m gay as hell and don’t try to hide it. And I’m not Christian. Oh, and I’m a bleeding heart liberal.

(Pause for one moment here and just think about radical butch mini-me growing up as a Junior Dyke in the Bible-thumping rural south. Yup.)

But my ancestry is (half) southern: My great-great-great grandfather was a prominent Georgia judge and plantation owner when the Civil War broke out; his daughter, Eliza Andrews, whose name I’ve commandeered to write lesfic (mischievous laugh) was a big supporter of the Confederacy, and his sons fought for the South.

You might think I’d be one of those “let’s preserve our heritage” whites. I’m not.

I could probably get into the Daughters of the Confederacy based on my bloodline; obviously, I don’t have the slightest interest in that. But when people talk about historic Civil War sites, when they talk about landowners who were bankrupted by the War, when they talk about monuments to Confederate soldiers, they are talking about my family.

But I think all those monuments to the Confederacy need to come down. Yesterday.

If that means relegating my own family to the moldy basement boxes of history, then so be it. If we are going to remember the Old South at all, let’s remember the mistakes that were made, so that history does not repeat itself.

You want to know why my family had blue blood? Slavery, y’all. Pure and simple.

I have this conflicted love/hate relationship with the South, and a love/hate relationship with my ancestry. On the one hand, it’s home; it’s what I know; it’s the land and the family that shaped me. And it burns my biscuits when people make blanket negative statements about southerners — that all southerners are bigots, or that all southerners are ignorant, or that southern culture is backwards. That’s a vast oversimplification and I always find myself defending southerners against these kinds of stereotypes. It also completely ignores the fact that a lot of Southern culture is inextricably intertwined with African American culture.

But it also burns my biscuits that a lot of (white) southerners try to frame monuments to the Confederacy as being about “heritage.”

Yeah, it’s about heritage. A heritage of slavery and abuse.

“No, no, no, the Civil War was fought over States’ Rights!” they say. “The monuments honor the people who fought and died for those rights.”

Yeah, they died for their rights. The right to friggin *own* another human being. The right to build your wealth on the backs of other people, who had no rights. The right to discriminate based on ethnic heritage.

Don’t gimme that “states rights” nonsense. The Civil War was fought over slavery, pure and simple. People like Eliza Frances Andrews didn’t want northerners coming in and telling them what to do, because what they were telling them to do was that it was time for slavery to stop.

Tear down the monuments.

Not only does honoring the Confederacy mean honoring and implicitly justifying slavery, the monuments also went up at specific times in American history for specific reasons. Primarily: To protest the civil rights gains of African Americans.

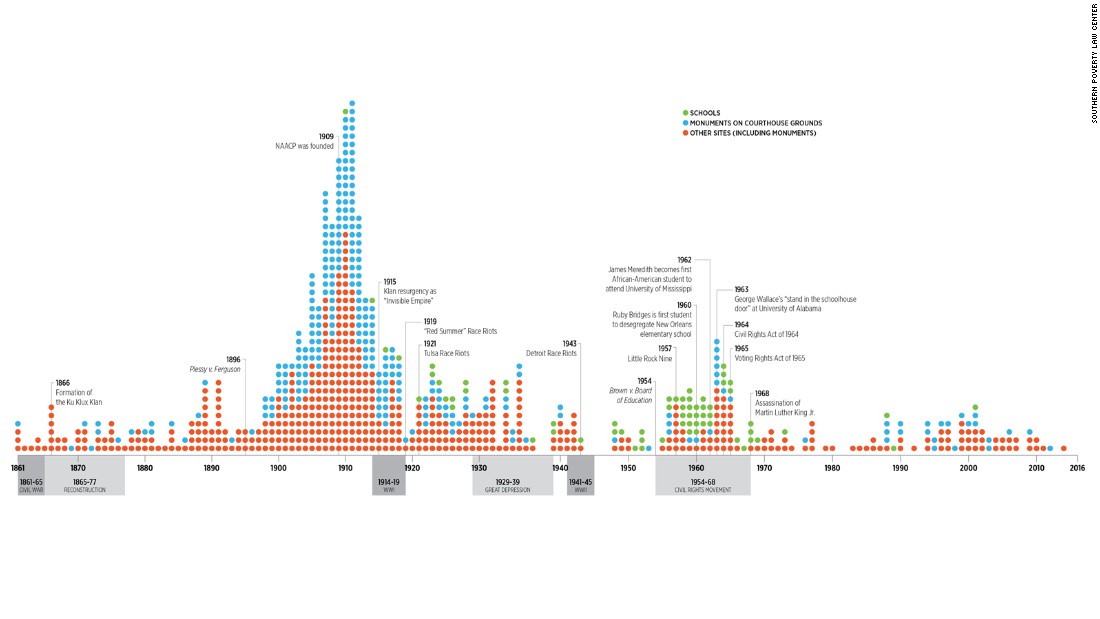

Take a look at this chart from CNN that shows when monuments to the Confederacy were created:

(That’s from this article on CNN.com about monuments to the Confederacy.)

I know you probably can’t see the chart, so I’ll just summarize for you.

That first big spike in the creation of all these monuments happened right about the same time when Jim Crow laws were first being instituted around the South and racial tensions were starting to seriously increase. By 1900, what you had was a lot of bitter white people who wanted to “Make the South Great Again” and go back to the more prosperous times when they didn’t have to pay their labor costs. You also had the formation of the NAACP in the same time period, so you’ve got African Americans really trying to assert their freedom and rights, which doubtless pissed off people like my Aunt Fanny (aka Eliza Andrews).

The next big spike happens right about the time you’ve got Brown vs. Board. The biggest spike in that time period happened the same year that Governor George Wallace tried to bar African Americans from entering the University of Alabama:

Let’s imagine we’re having this conversation in Germany.

Instead of focusing on the history of the United States and our Confederate memorials, let’s imagine all of this conversation happening in a different context.

I don’t know much about the history of Germany, especially modern Germany, but I know that a lot of my German friends seem to feel about World War II era Germany about the same way that I feel about the Civil War. That was their family that fought and died for the Nazi cause — their uncles and grandfathers and grandmothers who fought to defend their country, who lived through carpet bombing, who had to pick up the pieces after the war and during the occupation.

They empathize with the misery of their family and the sacrifices they made, but they also know the Nazis were wrong and evil.

But let’s pretend that, starting in the 1960s or 70s, groups of Germans who resented the demonizing of their brethren who fought and died in the war decided to start erecting statues to famous Nazis (for all I know, this happened — like I said, don’t know German history).

Imagine that in parks and in front of courthouses in certain parts of Germany, big bronze statues of Hermann Goring, Joseph Goebbels, and good ol’ Adolf Hitler himself started going up. Imagine flying the Nazi flag under the German flag to “honor our heritage.”

Probably, for a lot of (non-Jewish) Germans born after the time these imaginary statues went up, they probably wouldn’t even think twice about what the statues represented. “It’s about our history and our heritage,” they would say. “I don’t agree with the Nazis, but it’s still a part of who we are.”

But now imagine that you are Jewish and living in Germany, and all around you, you see images that remind you of the incalculable losses your people suffered during the war. You can’t even go to court without passing by a statue of Goring on the lawn outside.

Are you getting the picture yet?

If you are African American and living in the deep South, your reality is not that different from the scenario I just described.

I lived for three and a half years across the street from the South Carolina State Capitol. Daily, I would watch diverse groups of schoolchildren going to tour the grounds, and I would wonder to myself, “What do the African American kids think when they pass these statues of Confederate generals? When they see Strom Thurmond standing proud? When they see the Confederate flag waving in the front lawn?” (I lived there before Hailey took it down.) “What do their teachers tell them? Do they teach them that the Confederate battle flag only made a comeback during the Civil Rights era, when whites protested their ‘States Rights’ once again in the face of things like Brown v. Board?”

#BlackLivesMatter

Removing monuments to the Confederacy doesn’t eliminate racism, and it doesn’t address the underlying and ongoing systemic economic inequalities that consistently make it harder for minorities to claim their place at the table in the American “meritocracy.”

But it’s a start. It’s a step in the right direction, an acknowledgment that people like my great-great-grandfather and Eliza Andrews were *wrong.* They were wrong, and we need to admit that, and move on, and improve, and come together. And we need to stop glorifying a past that was based upon the rise of the few upon the backs of the many.

0 Comments